Local Sharks: Studying Sand Tiger Sharks

This is one of a series of posts by Associate Scientist Jeff Kneebone, Ph.D., about his work with sand tiger sharks. This post provides historical context about this species along the East Coast and in New England in particular.

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, July 12, 2017

New England is a region that has a rich history of shark activity. Not only do its waters support several shark species—from the small spiny dogfish to the massive basking shark—it was the setting for “Jaws,” the 1975 film that struck fear into the hearts of beachgoers and gave these fish the reputation as “man eaters” worldwide. Over time, as we’ve learned more and more about sharks, the public perception of them as mindless killing machines has generally faded and been replaced by a general fascination with this diverse group of fish. In recent years, one area where this fascination has been incredibly apparent is right here in New England, where public interest has focused primarily on the large white sharks that have taken up residency in our coastal waters. However, what most New England residents don’t know is that there is another lesser-known shark species that has also experienced a recent resurgence in the region, the sand tiger.

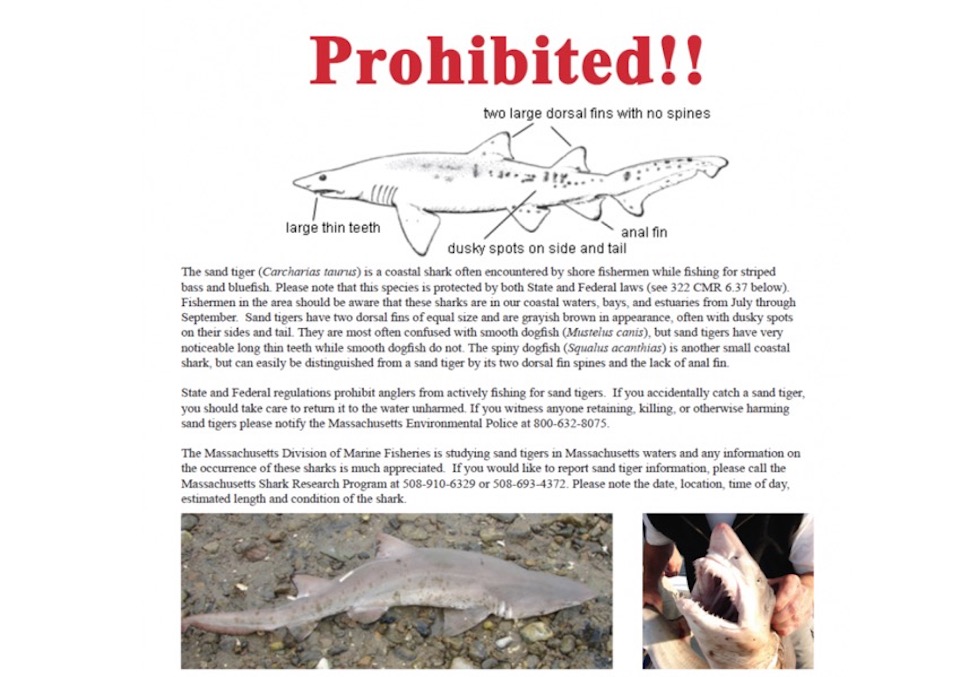

The sand tiger (Carcharias taurus) is a coastal shark species that historically has been known to migrate to New England waters seasonally during the months of June to October. While never historically encountered in abundance north of Cape Cod, sand tigers were once considered to be the most common species of shark in coastal nearshore waters of southern New England from Woods Hole to Nantucket. In fact, they were so abundant in this area that they were the target of a directed commercial fishery during the early 1900s. Unfortunately, owing to their low biological productivity—they mature at old ages and only produce two offspring every two or three years once they are reproductively active—sand tiger populations typically decline rapidly in response to sustained fishing pressure. This scenario has resulted in the decline of sand tiger populations throughout the world—including in Australia, South Africa, and South America—and was responsible for the depletion of their population along the U.S. East Coast by an estimated 70 to 90% from the late-1970s to the early-1990s. As a consequence of this population decline, sand tigers became rare throughout New England during this period, even in areas where they were once prolific. Fortunately, this population decline was acknowledged relatively quickly by federal and state fishery managers and conservation measures were enacted in 1997 and 2009 that prohibited the retention of any sand tiger in any fishery along the U.S. East Coast—in other words, all captured sand tigers must be released.

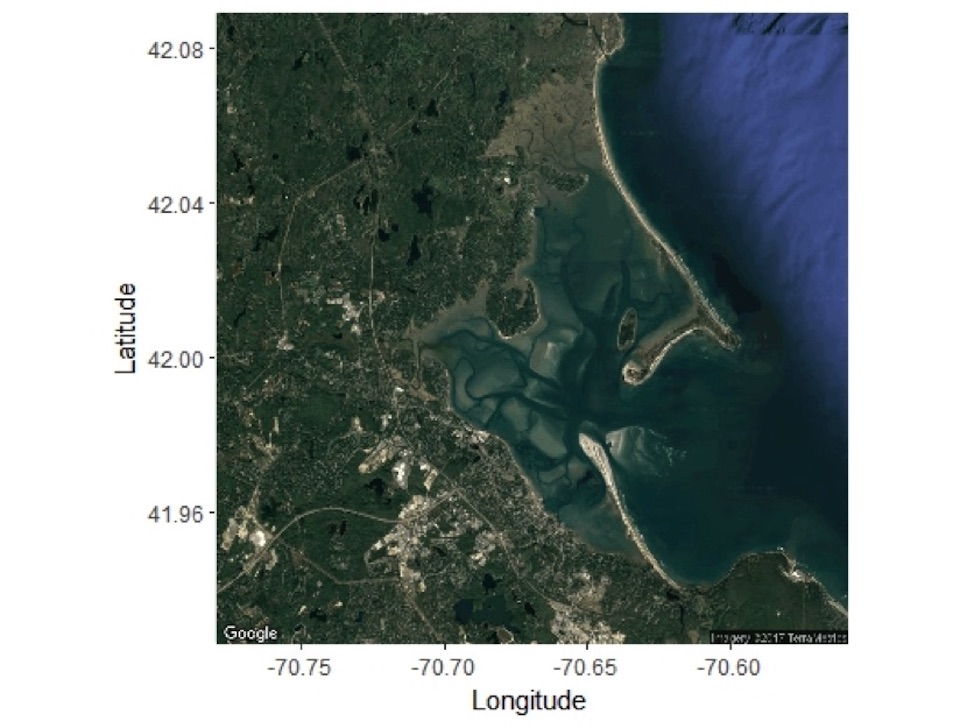

So where do we stand after two decades of sand tiger conservation efforts at both the federal and state levels? Well, in recent years fisheries capture records and scientific research data have provided strong indications that the sand tiger population along the U.S. East Coast is recovering, and one of the areas where this population recovery has been particularly evident is here in New England. Interestingly, however, this resurgence in New England has been especially evident in an unexpected place, the waters north of Cape Cod, where sand tigers were never historically found in abundance. In fact, based on catch reports from commercial and recreational fishermen, several areas north of Cape Cod have emerged as sand tiger “hot spots,” including Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury (PKD) Bay, a tidal estuary situated on the Massachusetts’ South Shore.

Beginning in 2002, John Chisholm and Greg Skomal of the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Shark Research Program started getting an increasing number of reports from local fishermen who were claiming to be catching sand tigers in PKD Bay. These reports were both interesting and puzzling for a few reasons. First, the local fishermen who were reporting the catches claimed that they’d never seen this species in abundance until recently, and second, sand tigers were not historically found north of Cape Cod, even in times of peak abundance. After collecting these reports for a few years, in 2006 John and Greg began working with local recreational fishermen Jay Hilliard and Dave Lindamood (aka “Santa”) and quickly confirmed that not only were there sand tigers in PKD Bay, there seemed to be quite a lot of them! Using National Marine Fisheries Service conventional shark tags, John and Greg began tagging sand tigers that were captured in PKD Bay and soon realized that all of the sharks they were tagging were juveniles of about 3 to 5 feet in length.

/

In late summer 2008, I joined John and Greg’s tagging project as a Ph.D. student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth School for Marine Science and Technology, and together we designed a study to answer some basic ecological questions about these juvenile sharks in PKD Bay including: How many sharks are in PKD Bay? When are they present in PKD Bay? What are their movement patterns? In what areas of PKD Bay do they spend most of their time? To answer these questions, we decided to employ a tagging technology called passive acoustic telemetry, which is like an E-ZPass system for fish.

Read Part 2 in the series of posts for more on the sand tiger shark research of Anderson Cabot Center scientist Jeff Kneebone, Ph.D.