Glowing Jellies, Growing Jellies: A Look at Jelly Culturing at the Aquarium

Aquarist Chris Doller is part of a team raising jellies at the New England Aquarium—including a jelly with a surprising ability.

By New England Aquarium on Tuesday, July 08, 2025

Behind the scenes at the New England Aquarium, aquarist Chris Doller cares for what some might think are a few of the ocean’s strangest inhabitants: jellies. There are thousands of different species of jellies that live in every part of the ocean, from the impressive Pacific sea nettle to the tiny and deadly irukandji, a type of box jelly. Currently, Chris cares for seven different types.

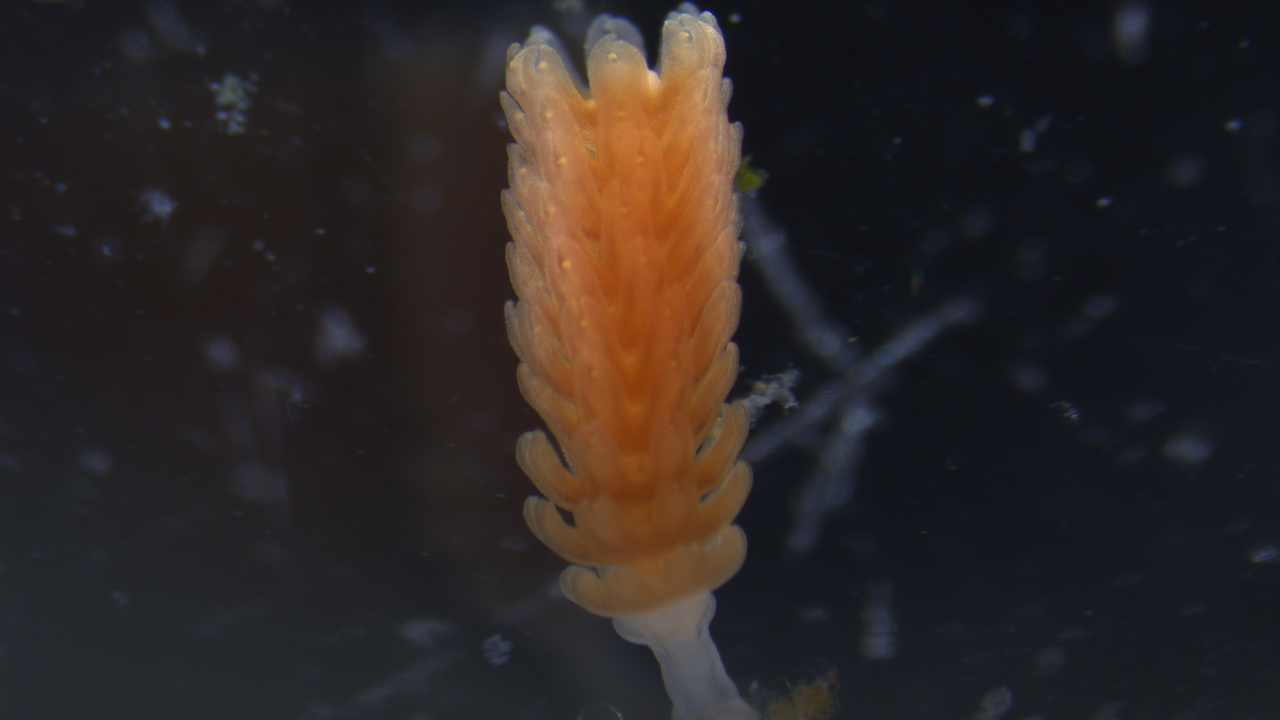

All sea jellies—commonly called “jellyfish,” though they aren’t fish—have several distinct life phases. What comes to mind when you think of jellies—an animal with a bell-shaped main body trailed by long, stinging tentacles—is the medusa or adult phase. Jellies also have an earlier polyp phase, during which they’re much smaller and mainly sedentary.

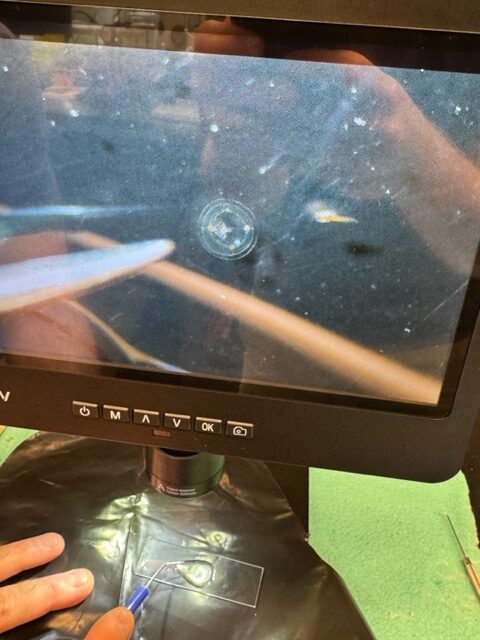

“What makes them an organism that we can culture is that we can keep colonies of them at that small stage behind the scenes,” Chris said. In the jelly lab, Chris and team carefully mimic conditions in the ocean that would trigger reproduction, changing the water temperature to simulate seasonal changes and causing the jellies to spawn.

“From there, it’s like growing plants—moving them to a bigger bowl, giving them a lot of love,” Chris said. He and the team adjust the growing jellies’ conditions, changing their food, water temperature, and water flow. “It’s a lot of work because they start so small. It can take months to get them to the size that they are out on exhibit.”

In addition to the jellies on exhibit, the team grows a whole family of jellies for display in jelly tubes, which our Conservation Learning team share with Aquarium guests to educate visitors about these animals. They also culture moon jellies as food for other jellies, occasionally sharing them among different institutions.

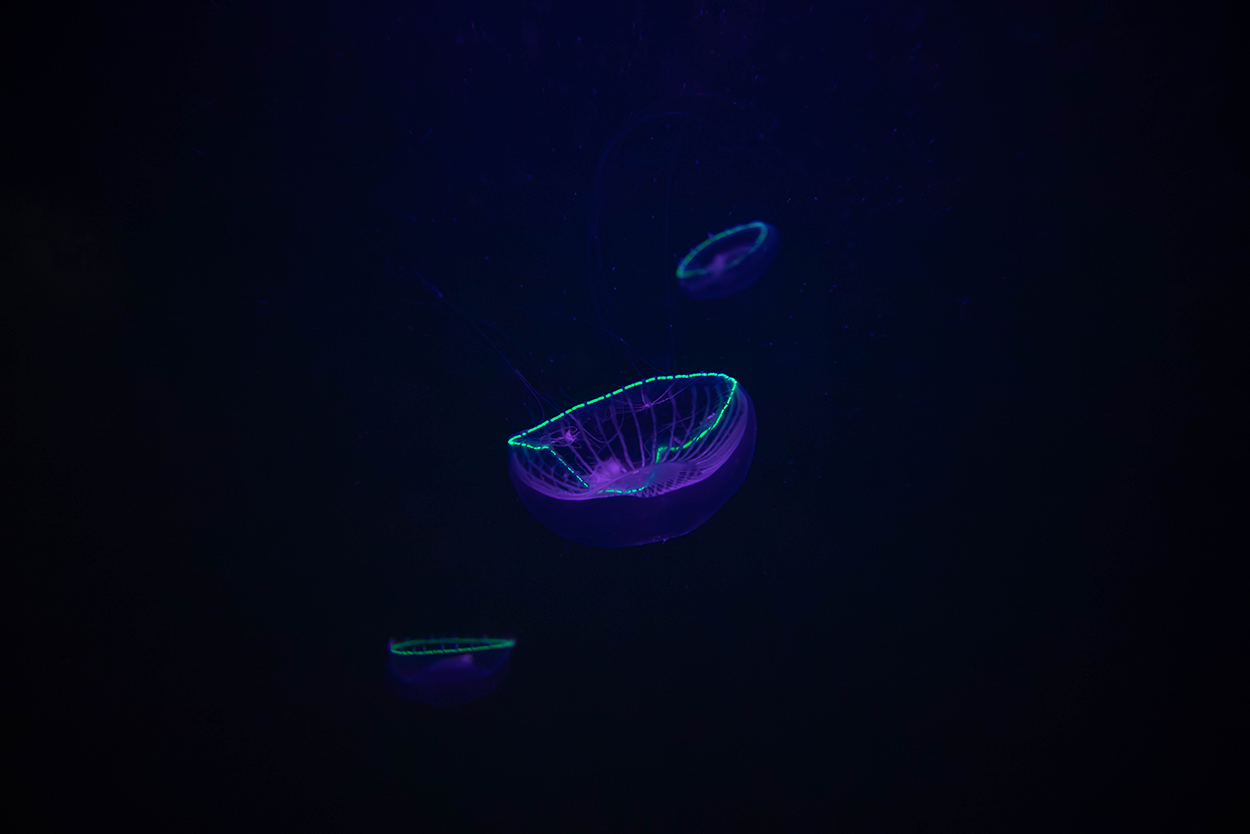

One of the more recent additions to the collection are crystal jellies. While they’re nearly transparent under normal light, crystal jellies glow green when illuminated under a blacklight—an ability Aquarium visitors can admire at our Sea Jellies exhibit.

Crystal jellies have this capability thanks to a luminescent protein in their bells. The green florescent protein, or GFP, is now used in medical research to study gene and cell expression. “A scientist out of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole was the first to isolate this GFP in crystal jellies,” Chris said. “He won the Nobel Prize for it.”

Comb jellies and Lion’s mane jellies are two other species that Aquarium visitors can often see on exhibit. All three are native to New England waters. During the summer, Lion’s mane jellies often attract a lot of attention—including a recent sighting of a giant jelly washed up on the shore in Maine.

“When it’s hot, people want to go to the beach, and it’s when jellies are present as well,” Chris said. While the Lion’s mane jellies “are quite stingy,” he added, overall, there’s some misunderstanding that all jellies are harmful to humans.

“Most jellies are very innocuous,” he said. “Some of them are completely stingless and not harmful at all.”

What can we learn from culturing jellies? “There’s a lot of experimentation,” Chris said. The jellies can be “somewhat mysterious,” remaining dormant for long periods of time—sometimes years—before spawning again.

In the ocean, jellies can display surprising resilience, thriving in conditions that are inhospitable to other animals—including warming and polluted waters. Changes to jelly health or abundance can potentially tell a larger story about the health of the ocean as a whole. “They’re very simple organisms. They have no brain; they have no blood. They just eat and reproduce, and that’s basically it,” Chris said. “They’ve been around since the dinosaurs.”

So: Has Chris ever been stung? “We wear protective equipment while we’re working with the jellies, but yeah,” he said. “It’s kind of a hazard of the job.”

Still, there are no hard feelings. The jelly that stung him—the flower-hat jelly, a species native to the waters of Japan, and one he hopes will soon be back at the Aquarium to begin culturing—is his favorite. “They’re just spectacularly beautiful,” he said.