Please note: We strongly recommend purchasing tickets online in advance to guarantee entry, as we do sell out on weekends.

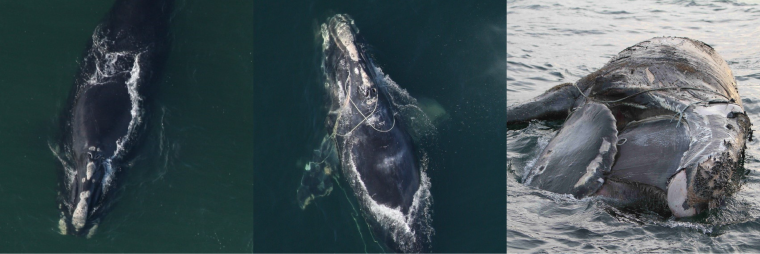

Health impacts from entanglements, including cases with only scars, are reducing survival and reproductive success in the critically endangered species

BOSTON, MASS. (June 14, 2022) – New research looking at the health effects of fishing gear entanglements finds North Atlantic right whales with severe injuries are more likely to die than those with minor ones, determining entanglements are now the leading cause of serious injury and mortality in the critically endangered species. The research underscores the urgent need for changes to the fishing industry as the species, with an estimated population of less than 350 individuals, faces extinction.

To examine the role fishing gear entanglements have played in right whales’ decline, scientists from the New England Aquarium and Duke University tracked the outcomes of 1,196 entanglements involving 573 right whales between 1980 and 2011 and categorized each run-in based on the severity of the injury incurred. The data revealed the health of right whales that experienced an entanglement deteriorated as injury severity increased. Male and female right whales with severe injuries, including cases without the presence of fishing gear, were eight times more likely to die than males with minor injuries, and only 44% of males and just 33% of females with severe injuries survived longer than 36 months. The study, published in Conservation Science and Practice, also found that sub-lethal effects of an entanglement on reproductive success are more pronounced than previously recognized.

“This species is heading quickly towards extinction because of human activities,” said lead author Amy Knowlton, a senior scientist at the New England Aquarium. “This study sheds further light on the role of fishing gear entanglements in their decline. Even if a right whale survives an entanglement, the injuries it sustains endure and can impact their health.”

Entanglements of North Atlantic right whales typically occur in fixed fishing gear, including lobster and crab pots and gillnets after the whale collides with ropes in the water. The resulting injuries can range from superficial wounds with no attached gear to cases in which the line becomes tightly wrapped multiple times around the whale, resulting in deep wounds, impaired feeding, and energetic costs caused by dragging the heavy gear. For this study, the researchers investigated the effects of all entanglements, including cases with only scars, which comprise the majority of documented entanglement events.

“Previous work has shown reduced survival when the whale is carrying gear, but what really surprised us was the reduction in survival regardless of whether gear was present, which was especially apparent in females,” said co-author Rob Schick, research scientist at Duke University.

Female right whales with severe injuries who survived had the lowest birth rates. As the health of reproductively active females declined, their calving intervals also increased, a worrisome trend for the long-term survival of the species.

Right whales face multiple stressors in the highly industrialized waters of the western North Atlantic, including collisions with vessels and entanglements in fishing gear. This critically endangered species is also facing the more recent effects of climate change, as food resources shift and become less predictable, though right whales have shown they have the ability to adapt.

What has been more challenging for this species to adapt to is changes in fishing activities, including expansion of fishing effort and strengthening of ropes. While most gear interactions result in only scars, the rate of serious entanglements—those with attached gear or severe injuries—has been increasing.

“If we are going to save right whales from imminent extinction, dramatic changes to how fixed fishing gear activities are presently conducted are needed. We believe these changes will require support from both the U.S. and Canadian governments to help the fishing industry transition to gear that will allow the industry to operate in a manner that is safer for whales and other marine species,” Knowlton said. “The New England Aquarium has been actively engaged in solutions for four decades, including promoting ropeless fishing methods and reduced breaking strength ropes. We are committed to continuing this collaborative work to save this species from extinction.”

Knowlton and Schick conducted the new study with James Clark of Duke’s Nicholas School, and Philip Hamilton, Scott Kraus, Heather Pettis, and Rosalind Rolland of the New England Aquarium.

MEDIA CONTACT:

Pam Bechtold Snyder – psnyder@neaq.org, 617-686-5068