Construction Update: As we enhance the look and feel of the Aquarium and make structural improvements to the penguin exhibit, some exhibits are temporarily closed, and the penguins are off exhibit until February 13. Learn more.

Everybody Poops—Even Whales

Whale poop plays an essential role in ocean ecosystems and research.

By New England Aquarium on Monday, February 09, 2026

It has been famously noted that “everybody poops”—and whales are no exception. From the smallest mollusks to the largest animals on Earth, digestion is a fundamental part of life. For baleen whales, however, this biological process plays an outsized role in the health of the ocean.

Scientific studies have revealed that whale digestion, and what comes afterward, does far more than support individual animals. It helps move nutrients through the ocean, supports healthy marine ecosystems, and provides researchers with valuable clues about whale health and behavior.

What whales eat

To understand whale poop, we first need to understand what whales eat. Baleen whales—a group of whales that includes right whales, fin whales, humpback whales, and the largest animal to ever live on Earth, the blue whale—do not have teeth. Instead, they take giant mouthfuls of ocean water and use baleen, a series of whisker-like plates, to filter out the water and trap their primary food source, zooplankton.

Many baleen whales are seasonal eaters, gobbling up food during summer mating season and relying on stored blubber for energy the rest of the year. But when they do eat, it’s a feast. On feeding days, a whale can consume up to 30 percent of its body weight in zooplankton.

The zooplankton paradox

With the rise of commercial whaling in the 19th century, whale populations declined dramatically. By the time international regulations were introduced, many whale populations were nearing extinction. At first glance, it might seem that zooplankton would thrive as one of their major predators disappeared. Instead, the opposite occurred. As whale numbers fell, zooplankton declined as well. Why? The answer lies in how whales help fuel the food that zooplankton depend on, a nutrient cycle known as the whale pump.

The whale pump

Whale waste is rich in iron, a nutrient that plays an important role in ocean life. Phytoplankton—microscopic, plant-like organisms near the ocean’s surface—need iron to grow. Zooplankton feed on phytoplankton and are then eaten by whales and other marine animals.

When whales eat large amounts of iron-rich zooplankton in deeper water and return to the surface, they release waste that brings iron back into surface waters. There, it acts like a natural fertilizer, fueling phytoplankton growth. That growth supports zooplankton populations, and, in turn, the whales and other animals that depend on them. This continuous recycling of nutrients is known as the “whale pump” (sometimes more casually called the “poop loop”).

By moving iron from deep waters back to the surface, whales help support the base of the marine food web. When whale populations decline, this nutrient cycle is disrupted, affecting far more than whales alone.

Whale health…

At the New England Aquarium, whale poop plays another important role: helping scientists assess whale health. While you can’t go up to a large whale and take a blood sample, poop samples offer a non-invasive way to gather critical biological data.

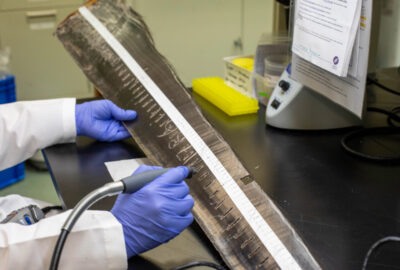

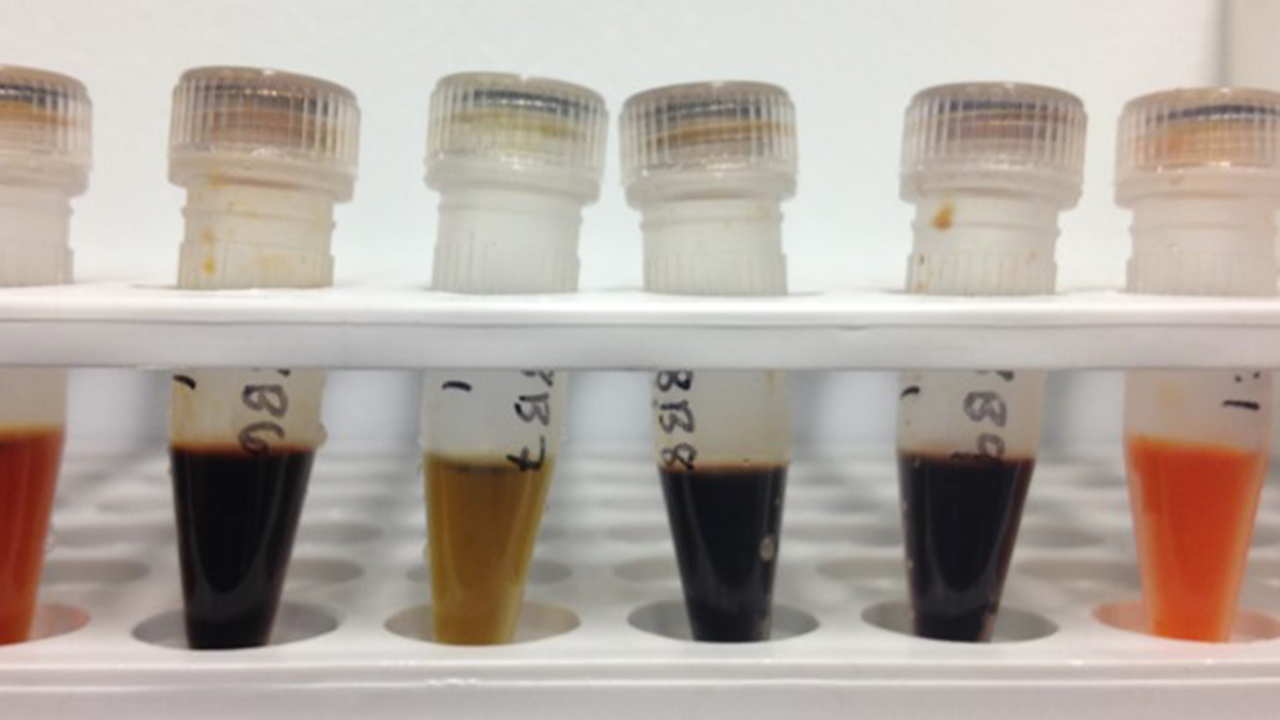

Researchers from the Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life collect samples during field work by spotting, and sometimes smelling, North Atlantic right whale poop at the ocean’s surface. They use a specialized net to collect the material, which is then transferred into individual containers and preserved in different ways depending on the analyses to come.

Fecal samples provide insights into a whale’s diet, gut microbiome, stress levels, growth, and reproductive status. Hormones such as progesterone and testosterone can indicate pregnancy and reproductive activity, while cortisol and corticosterone reflect stress. Thyroid hormones offer clues about metabolism and growth. The presence of plankton species in feces helps researchers understand what whales are eating and whether they’re finding enough food.

This information is especially important in regions such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where right whales are increasingly spending time. Researchers need to determine whether these newer habitats provide sufficient nutrition.

All of this in service of a better understanding of these marine giants, and with each recovered stool sample we get one step closer to helping their populations recover.

…Is ecological health

The health of whales and the health of the ocean are deeply interconnected—and that connection ultimately extends to us humans.

Phytoplankton, though they make up just about one percent of the Earth’s total biomass, produce roughly 50 percent of the oxygen we breathe. They are also one of the planet’s most powerful carbon skins, absorbing large amounts of carbon dioxide and storing it in their bodies rather than allowing it to accumulate in the atmosphere and accelerate climate change.

By helping whale populations recover, we support the natural nutrient cycles that fuel phytoplankton growth, stabilize marine ecosystems, and contribute to a healthier planet each time nature calls.