On Thursday, February 12, the Trust Family Foundation Shark and Ray Touch Tank will be closed until 10:30 a.m. for routine animal care

Construction Update: As we enhance the look and feel of the Aquarium and make structural improvements to the penguin exhibit, some exhibits are temporarily closed, and the penguins are off exhibit until February 13. Learn more.

Inside the Wildlife and Ocean Health Lab

At the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, scientists are delving into the powerful world of hormones extracted from biological samples—working to unlock key insights to help protect the blue planet.

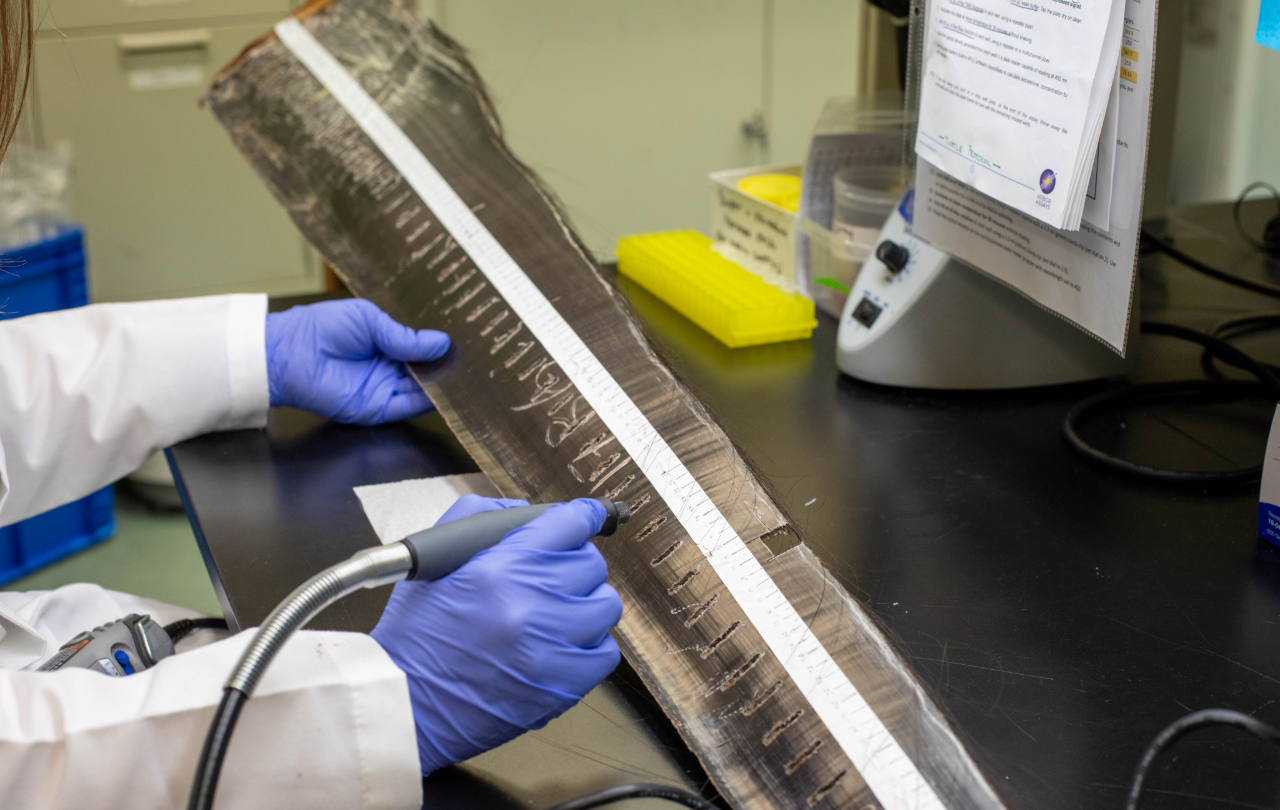

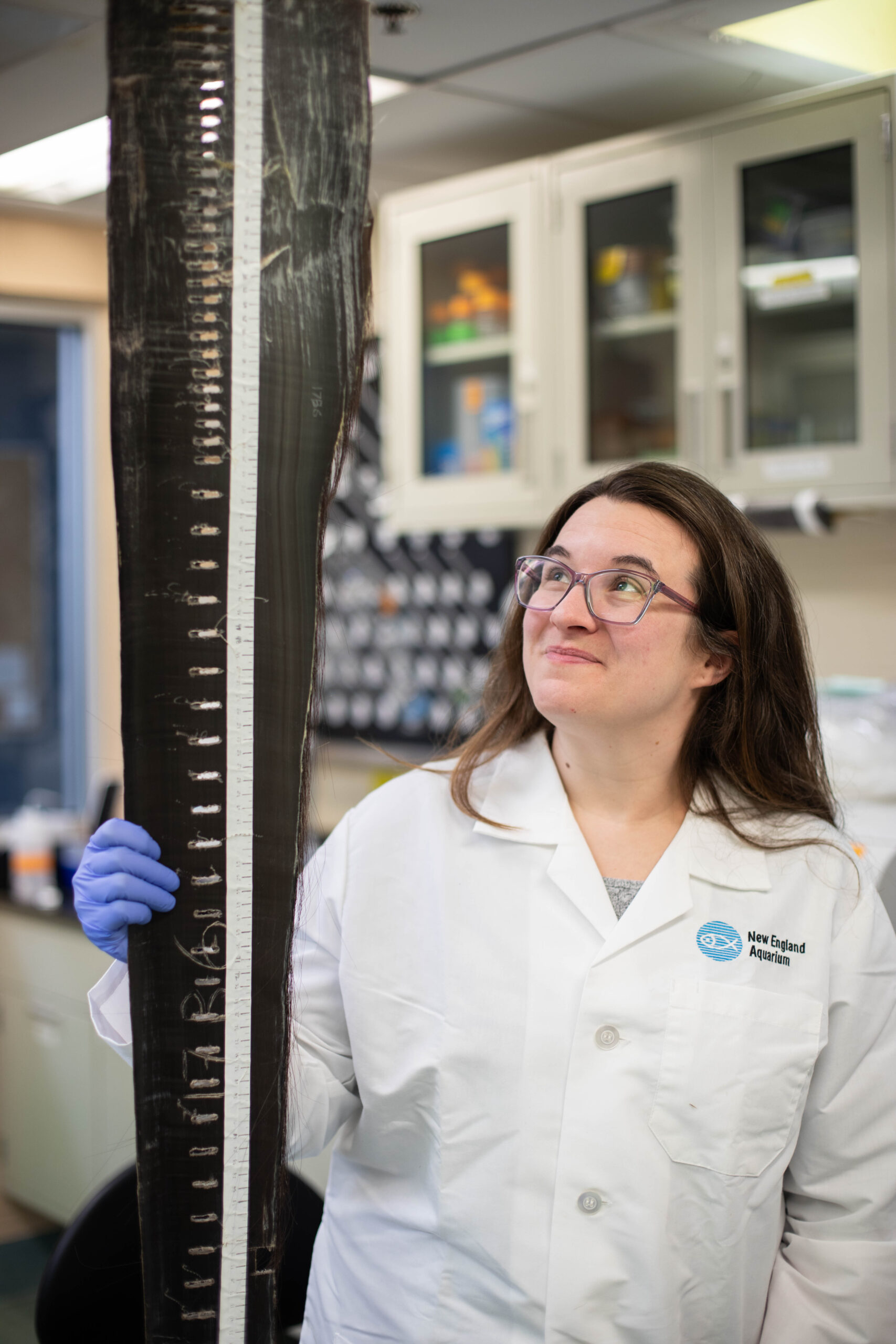

Behind the scenes at the New England Aquarium, in the laboratory, Danielle Dillon is surrounded by samples to study—from blubber and skin collected from right whales to blood plasma from sea turtles, six-foot pieces of baleen, and fridges packed with poop. As an associate scientist in our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, it’s Danielle’s job to carefully process and analyze each of these samples, looking for clues in the hormones they contain. These hormones can help paint a picture of an animal’s health, allowing researchers to answer important questions about these species—and even get insights into major events in an animal’s life.

Stories in the samples

“All of these sample types represent a different moment in time,” Danielle explained. “So we can ask: What is an animal experiencing right now? How has it been feeling for the past couple days, or even the last month? Or, in the case of baleen, what has this whale experienced over the past seven to 10 years?”

What Danielle and her team “see” in each sample are hormones, such as testosterone and progesterone, which are associated with reproduction, and cortisol, which is linked to stress. By measuring these hormone levels and interpreting their patterns, Danielle can infer crucial information about an animal’s life.

For example, have they been pregnant? Did they experience significant stress due to an injury? Or simply, are they healthy and well-fed?

The samples Danielle analyzes come from a number of sources, many from fellow researchers at the Anderson Cabot Center. Right whale scientists collect skin biopsies, poop, and blow samples during fieldwork to monitor the health and reproduction of marine wildlife. By studying changes in hormones among individual right whales, researchers can create an “early warning system” to signal challenges the population might be facing, whether from human activity in the ocean or food scarcity.

Getting results

But how do you get results from a piece of right whale baleen or frozen fecal sample? “Chemistry!” said Danielle. The process involves freeze-drying to remove water, turning the sample into a fine powder, and carefully measuring out a tiny portion. This powder is then mixed with a solvent to help separate the hormones from the rest of the material in the feces. At this point, using the resulting liquid, Danielle can perform an enzyme immunoassay, or EIA, which uses antibodies to detect specific molecules in the sample.

Danielle shared a time-lapse video showing a tray of samples turning from blue to various shades of yellow. “At the end, the color change is an inversely proportional reaction to the amount of hormone present,” she explained. “If you have a ton of cortisol in a sample, the color change is minimal. But if there’s only a little bit of cortisol, the color change is significant.”

By pairing the results of the EIA with known information about the animal—such as body condition, location, and any injuries—researchers can reveal a much deeper story than what is observed at the surface. In some cases, these insights reveal previously unknown details. Working with a sample of baleen collected from Snowplow, an 18-year-old female humpback whale that washed up on a New Hampshire beach in 2016, Danielle and a research intern discovered evidence of a pregnancy that had not been documented.

“Humpback whales are a protected species, so it was important that we learn as much as we could from this great whale. It was an awesome discovery,” Danielle said.

Often, Danielle and her fellow researchers in the lab are analyzing samples collected years ago—like Snowplow’s baleen—to answer questions that can help inform current efforts. Thanks to scientific advances, researchers can now revisit past events with new tools, gaining deeper insights into long-term environmental impacts and guiding future conservation work. In early 2024, the lab contributed to a study on endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles that were rescued after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The oil-exposed turtles were treated, and blood samples were collected for medical evaluation. After 11 years in the freezer, the samples were analyzed for hormone levels using a novel test recently developed by our scientists.

The findings revealed that oil-covered turtles had abnormally elevated hormone levels, which returned to normal after rehabilitation and their eventual release. This finding underscores the effectiveness of rehabilitation in restoring the health of the turtles. “The hormone tests we used in the study weren’t yet validated for sea turtles at the time of the oil spill,” said Dr. Charles Innis, a senior scientist and veterinarian in the Anderson Cabot Center, who led the study. “It highlights the importance of preserving samples so that future technologies can be used to provide further insight into past events.”

New methods, New opportunities

Anderson Cabot Center scientists are continuing to deploy emerging technologies, most recently by using drones to collect samples of blow from large whales. Studies to date have predominantly relied upon using a 30-foot-long pole to collect whale blow for hormone studies. In 2024, Danielle analyzed drone-collected blow from fin whales and found that the fast-flying drones were effective at capturing a usable hormone sample from a swimming whale. That opens up opportunities to share samples with other institutions for further study and learn even more about individual whales’ health.

Another project from Danielle’s lab focuses on animals a little closer to home—northern fur seals that were under our care at the Aquarium during the COVID-19 pandemic. Working alongside the Animal Care staff, Danielle is processing fecal samples collected over several years to understand how this prolonged public closure affected the fur seals.

“When the Aquarium closed due to COVID, the animals also experienced that,” said Danielle. “What was their experience? We’re curious if this is reflected in their fecal samples. It’s a cool question we get to explore.”

Each of these questions—and the answers they uncover—give Danielle and her team a glimpse into the lives of animals, helping to drive forward our understanding of conservation and animal care. “The more we learn about the health, reproduction, and stressful experiences of marine animals, the better equipped we are to protect them,” Danielle emphasized. “Every discovery, no matter how small, brings us one step closer to a future where these vulnerable species can thrive.”

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of blue member magazine.