Monitoring a Species

Through long-time collaborations, our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life scientists study right whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

By New England Aquarium on Friday, February 16, 2024

Since 2015, North Atlantic right whale scientists from our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life have been conducting summer field research in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence. During fieldwork, our scientists often collaborate with other US and Canadian organizations in order to identify these critically endangered whales, collect biological samples, and study the population in this important seasonal habitat.

Associate Research Scientist Kelsey Howe and Research Technician Kate McPherson participated in separate research trips this past July. While the pair confronted weather challenges, each spent many days out on the water doing research and spotting right whales. “These trips highlight how important it is for the Aquarium to have a presence in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and for us to be doing boat-based research,” Howe said. “We have a lot of right whale and photo-ID experience and, thanks to that, are able to gather important information on new injuries, scarring, and health.

Studying, photographing, and collecting samples

Howe collaborated with the Canadian Whale Institute (CWI) and Fédération Régionale Acadienne des Pêcheurs Professionnels, focusing on right whale photo-identification as well as collecting biological samples from right whales. The core team of four researchers worked from a small rigid-hull inflatable, the FRC Charlie, running day trips out of Shippagan, New Brunswick, to the Shediac Valley in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. “The benefit of a small, fast boat is it’s more maneuverable and easier to get close to whales for sampling,” Howe said, “but the downside is you are much more limited by bad weather.”

Despite the weather, which was often too windy or stormy for an excursion, the team managed 13 survey days for the month. The poor conditions included five straight days of fog, an unusual occurrence in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, “but we were still able to find whales in the fog!” Howe said. “If you are near an aggregation when the fog rolls in, you can find them by listening for their blows.”

Throughout the survey days, there were 52 individual right whales photographed, including sponsorship whale Manta (Catalog #1507). “These photographs provide lots of important health and scarring information—evidence of injuries or entanglements,” said Howe. Other familiar faces spotted included Wolf (Catalog #1703), Harmonia (Catalog #3101), and Shelagh (Catalog #4510). In a particularly fun moment on the vessel, two-year-old right whale Catalog #5140 came over and curiously swam around the boat a few times!

Howe and the team also sighted Catalog #4042, a whale that, a week after their sighting, was spotted entangled in fishing gear. Aquarium scientists were able to confirm the identity of the entangled whale as Catalog #4042, the 13-year-old son of “Ravine” (Catalog #3142), initially by a description over text. The Dalhousie University team that discovered the entanglement was able to track the whale for ~20 miles until sunset. A disentanglement team rallied on land the following day but, due to strong winds, were unfortunately unable to mount a response. By early September, another vessel spotted Catalog #4042, having apparently shed the gear. “This whale is one of the ‘lucky ones,’” Howe said. “Oftentimes when a whale is sighted entangled, we either see them again in poor health or never again.”

Tracking right whales with short-term tags

McPherson’s work in the Gulf of St. Lawrence was a collaborative tagging project led by Dalhousie University and the University of New Brunswick, with a tagger from NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a tag boat driver from CWI. McPherson was on the smaller of two boats on the project, and her research trip was just 10 days long, with four days out on the water. But in that limited time, the team accomplished a lot.

“I took photos of each whale that was approached by the tag boat to determine if the whale was a good candidate for tagging,” McPherson said. “We only want to place tags on healthy whales—individuals without injuries who have good body condition—and we don’t want to accidentally tag the same whale twice. It’s important to have someone on the boat who can identify individuals and assess health!”

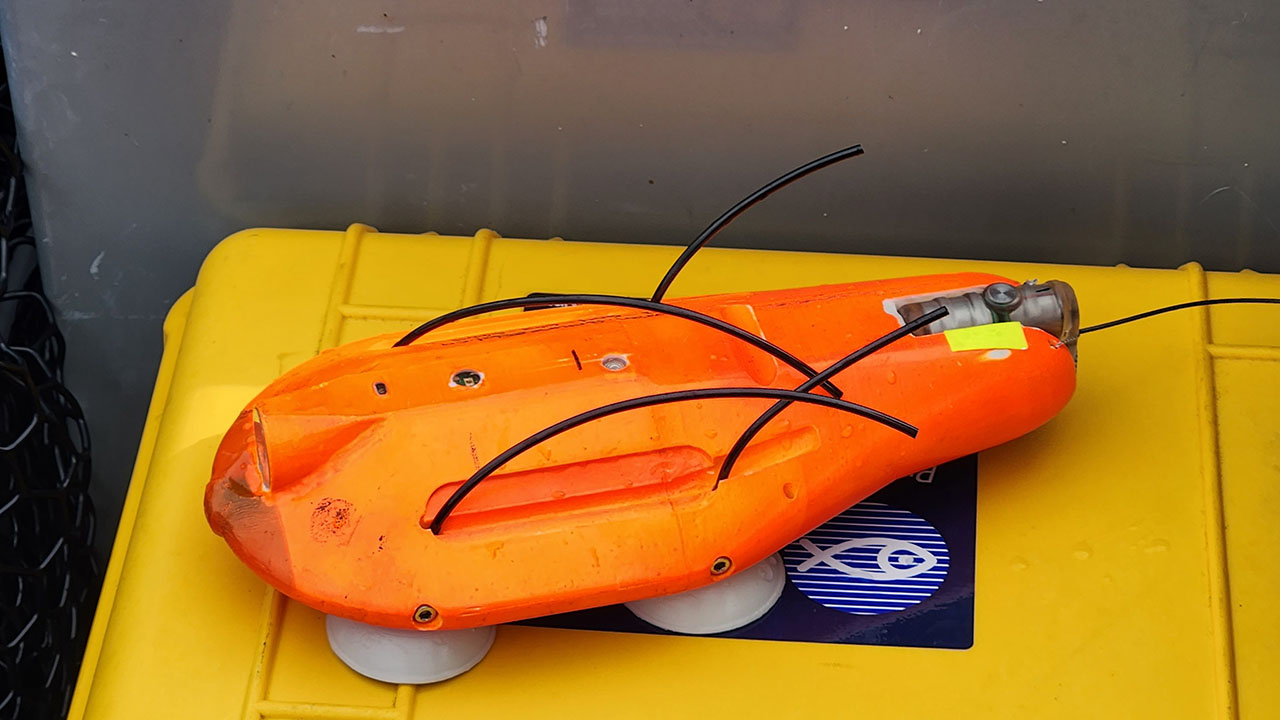

The tagging team was able to place suction cup tags on four right whales: Wishbone (Catalog #4640), Squilla (Catalog #3720), Bocce (Catalog #3860), and the 2020 calf of Harmony, Catalog #3115. The suction cup tags recorded the movement of the whales in areas where they were feeding below the surface to get a better picture of their activity around prey fields. Tagging a whale takes patience, persistence, and a lot of skill. The suction cup tag is placed on the back of the whale with a long pole and stays on for several hours before falling off, floating to the surface, and being retrieved by the research team.

In the same locations where the whales were tagged, the team conducted oceanographic sampling to get a better sense of what the whales were feeding on. “There were tons of copepods in the area,” McPherson said, which is an important food source for right whales. New mom Smoke (Catalog #2605) and her 2023 calf were spotted by the team in the area. “They both looked healthy and with any luck, Smoke was feeding on all those copepods to replace her fat stores after nursing this calf since December,” McPherson added.

Thanks to a last-minute invitation from the CWI team, McPherson was able to go out for one final survey day before returning to the United States.

Our researchers are always on alert for new injuries or entanglements during surveys. During that final day, McPherson and the team came across a well-known female, Chiminea (Catalog #4040), with a new cut on her right fluke. “Photographing and documenting Chiminea’s injury helps researchers determine the severity of the wound and gives us a timeframe of when she was injured,” McPherson said. The nature of her injury made Chiminea easy to single out among the other whales, giving the team an opportunity to photograph her thoroughly. Chiminea last gave birth in December 2020, and as one of the few remaining reproductive North Atlantic right whale females, her health is extremely important to the future of this species.

“At the time, we were the only team to have documented Chiminea in the Gulf of St. Lawrence with this new wound,” McPherson added. “While moments like these are disheartening, it highlights the importance of us being out on the water as much as possible to document these injuries.”