Tag! You’re it!

New insights into the movement patterns and habitat use of thorny skate in the Gulf of Maine based on nearly 20 years of cooperative tagging effort.

By Jeff Kneebone, PhD on Friday, October 30, 2020

This is Part III of a series of blogs about research on thorny skate in the Gulf of Maine being led by the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium. This post describes the results of the tagging study introduced in Part II.

Thorny skate (Amblyraja radiata) have experienced decreasing abundance and range contraction in the Gulf of Maine (GOM) in recent decades. The factors driving these trends are not fully understood, partially due to the limited understanding of thorny skate population structure, habitat (depth and temperature) preferences, and movement patterns in the region. For example, it is not known if individuals inhabiting the GOM represent a single population, or if they freely exchange with other thorny skate throughout their broader western North Atlantic range.

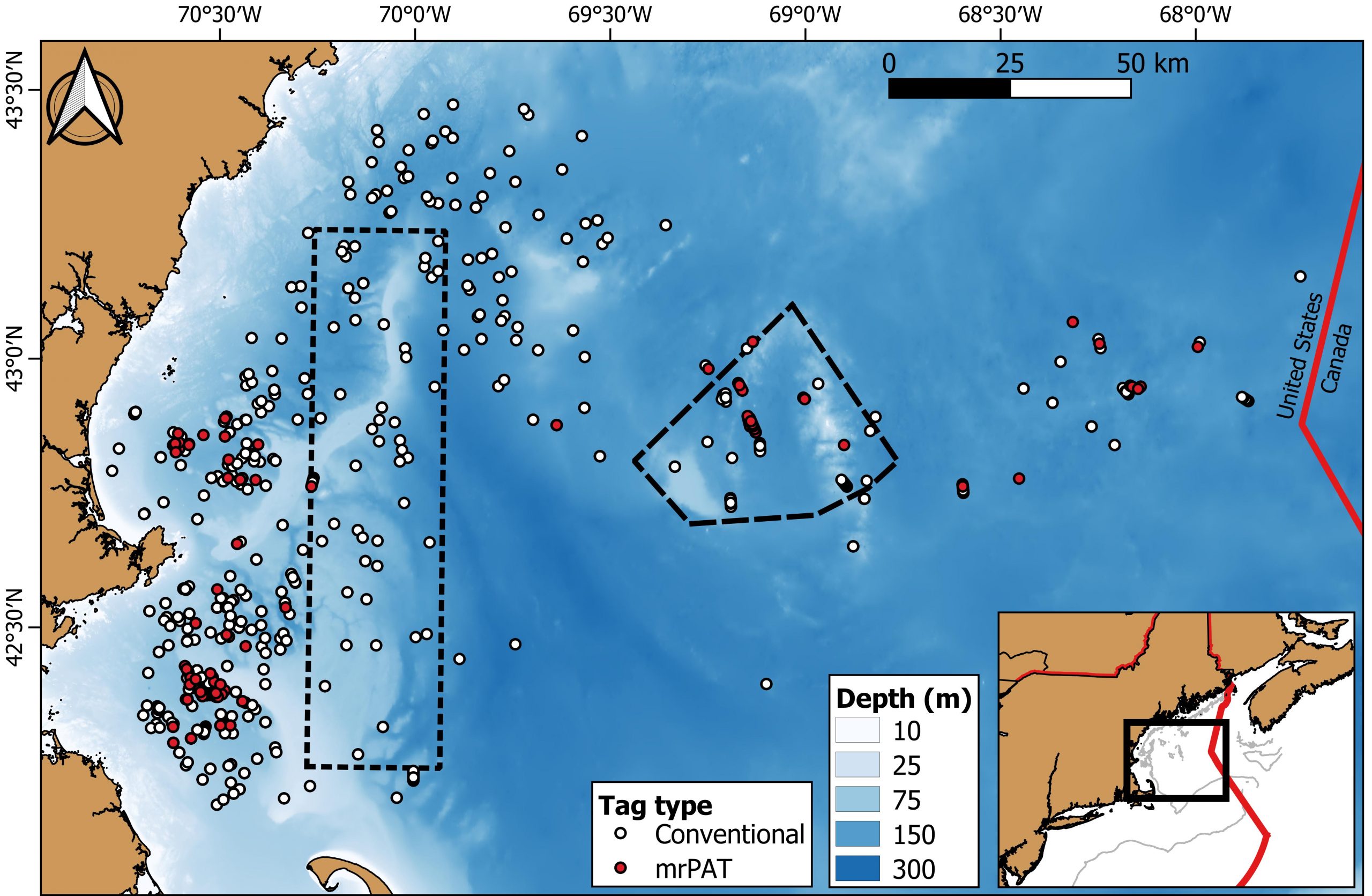

To improve our scientific knowledge of the species, a team of researchers led by the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life deployed nearly 2,400 tags on thorny skate in the GOM from 2002 to 2019. The majority of these tags were ‘conventional’ style identification tags that provide information on a skate’s movement if they are recovered or recaptured – that is, their movement from the point of release to the point of recapture. However, over 100 were small, ‘mark-report’ pop-up satellite tags (mrPAT) that provided information on skate movements (from the point of release to tag reporting) and daily temperature occupied over periods of 30 to 300 days.

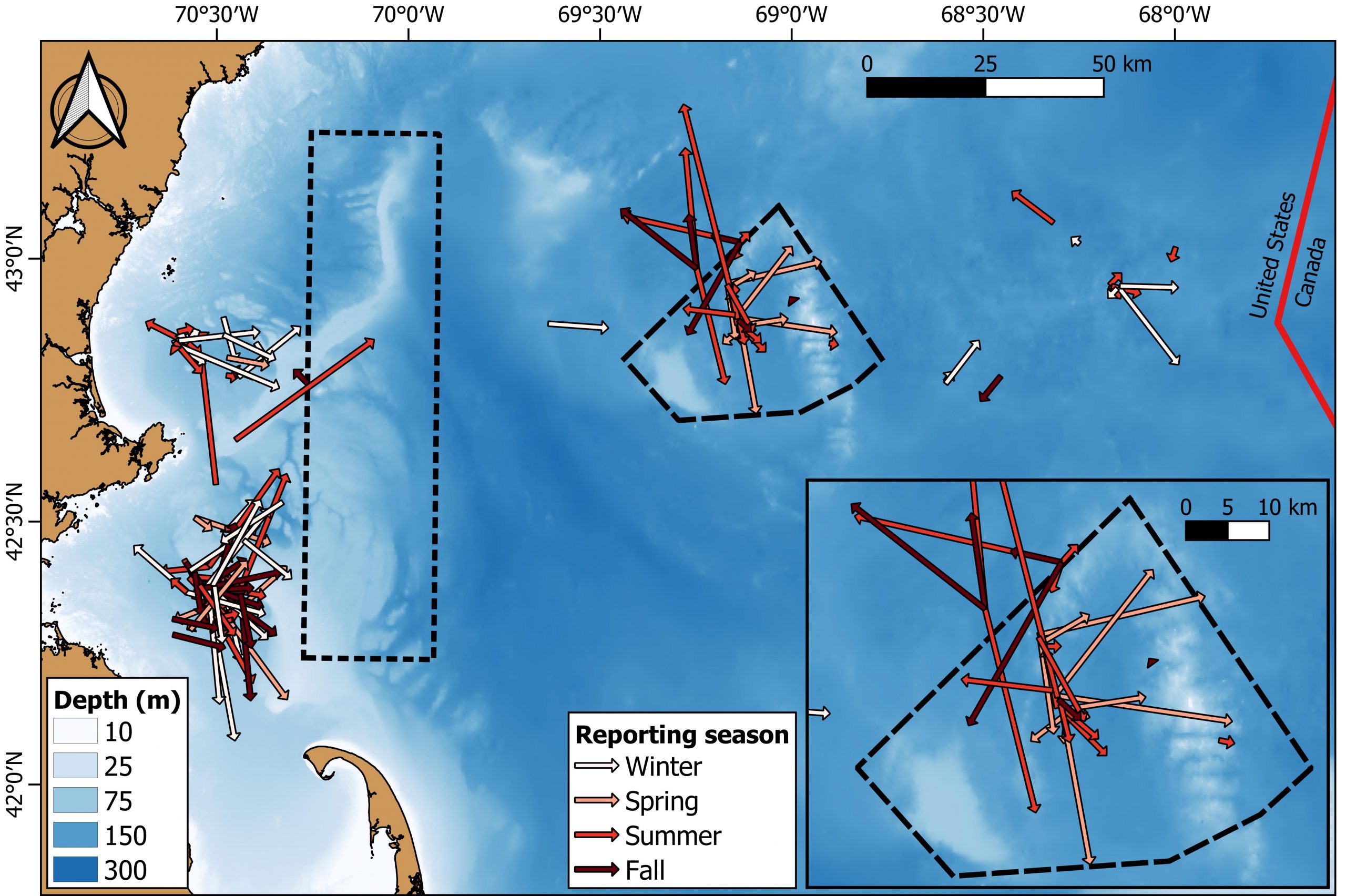

Movement data obtained from 84 mrPAT reports and 43 conventional tag recaptures – representing 55 male and 72 female skates measuring 32 to 104 cm in length – revealed that thorny skate generally do not move much within the GOM in both the short and long term. In fact, tagged individuals only moved 0.4 to 46.8 km from their release locations over periods of up to 3,435 days (that’s over 9 years)! Skates were observed at depths of 27 to 201 m and in water temperatures of 2.5 to 12.5 °C, with fluctuations in both depth and temperature evident by season.

Given their restricted movements over both short- and long-time periods, thorny skate may exist as a single population in the GOM. However, additional genetic testing is required to confirm this hypothesis. The pervasiveness of sedentary behavior may also place the species at risk of localized depletion and climate change, but also demonstrates the potential efficacy of spatial closures for promoting population recovery. For example, 90% of the skates tagged with mrPATs in the Cashes Ledge Closure remained within the closure area over periods of 100 to 300 days, which is a behavior that shelters them from being accidentally caught by fishermen.

You can read more about this research in an article published in the ICES Journal of Marine Science.

This research was supported by NOAA’s Saltonstall-Kennedy Grant Program and Bycatch Reduction and Engineering Program as well as the former Northeast Consortium. It also involved critical collaboration with local commercial fishermen, the NOAA/Northeast Fisheries Science Center Cooperative Gulf of Maine Bottom Longline Survey, and the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Atlantic Cod Industry Based Survey.

Scientific and Industry Collaborators: Dr. Jeff Kneebone, Dr. John Mandelman (Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life); Dr. James Sulikowski (Arizona State University); Ryan Knotek (University of Massachusetts Boston); Dr. Dave McElroy, Brian Gervelis (NOAA Cooperative Research Branch); Dr. Tobey Curtis (NOAA Fisheries); Captain Joe Jurek (F/V Mystique Lady); Captain Phil Lynch (F/V Mary Elizabeth); Captain Eric Hesse (F/V Tenacious II); Bill Hoffman, Nick Buchan (MA Division of Marine Fisheries)