Please note: We strongly recommend purchasing tickets online in advance during the heat wave, as our ticket booth is located outdoors.

Night Owls: Tags Reveal Higher Nocturnal Activity in Juvenile Sand Tiger Sharks

By Jeff Kneebone, PhD on Tuesday, November 20, 2018

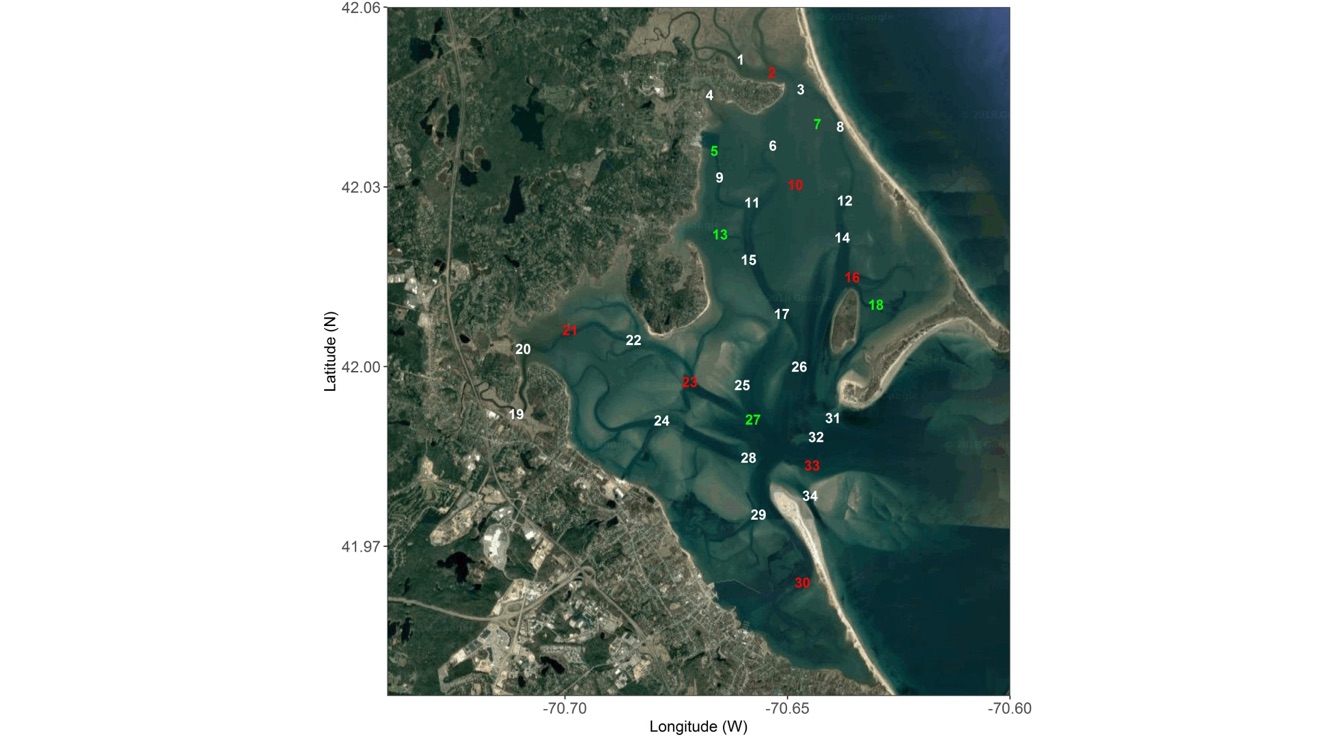

Over the last decade, juvenile sand tigers (Carcharias taurus) have re-emerged as one of the most common shark species in Massachusetts coastal waters. Previous and ongoing tagging efforts by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life have revealed that some areas, such as Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury (PKD) Bay, are summer nursery grounds for these young sharks.

While we now know a bit about where the sharks like to hang out off the Massachusetts coast, we don’t yet have a good understanding of why they return to specific places year after year, or what they’re doing when they’re in those places.

To learn more about this, in summer 2011—while I was a student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth School for Marine Science and Technology—I worked with colleagues from the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and University of Massachusetts Amherst to study the activity patterns of juvenile sand tiger sharks in PKD Bay. To do this, we used acoustic transmitters that were equipped with depth and tri-axial acceleration sensors—think of them as tiny Fitbits for sharks.

These small electronic tags record and transmit detailed data on shark swimming activity and swimming depth that can be detected and logged by a network of acoustic receivers placed throughout the bay, much like how an E-ZPass works on a highway, but the system is for sharks instead of cars. Data logged by the receivers are downloaded and analyzed with sophisticated statistical models to examine general patterns in activity over long periods (weeks to months) and investigate how certain environmental conditions, such as water temperature, tide stage, and moon phase, affect the shark’s behavior and activity.

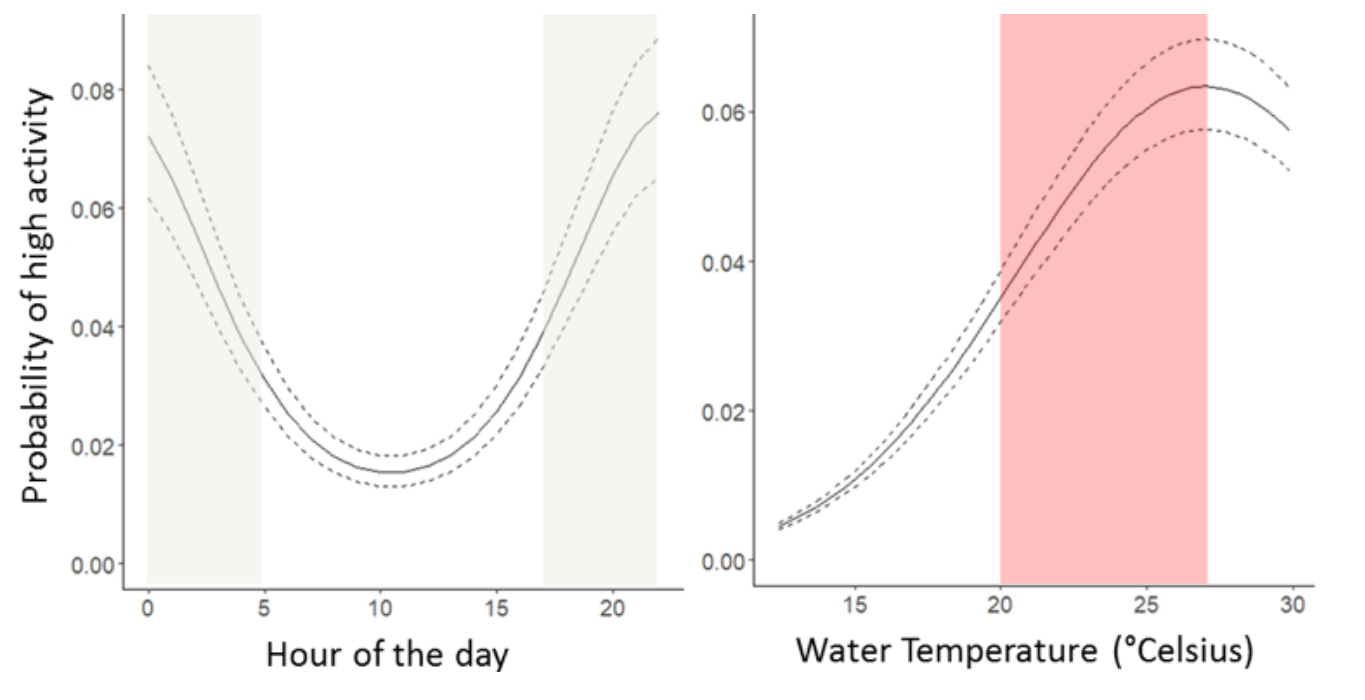

Using acceleration and depth data that were collected from eight juvenile sand tigers within PKD Bay during summer 2011, we determined the sharks spent the majority of their time slowly swimming near the bottom of the bay, but swam more actively and toward the surface at night. Sharks were also more active during the new moon phase and at some of the highest water temperatures experienced in PKD Bay.

Juvenile Sand Tiger Shark Swims in Tank

Juvenile sand tigers spent the majority of their time swimming slowly near the bottom in PKD Bay. They even spent some time resting motionlessly on the bottom! This video shows a shark exhibiting this behavior in the bottom of a tank. Video Credit: Alex Mansfield, Jones River Environmental Heritage Center.

Based on these results and our observations of juvenile sand tiger movements in PKD Bay, we hypothesized that the sharks are actively feeding during the periods of highest activity, perhaps taking advantage of low light conditions during the nighttime hours—particularly during the dark, moonless nights of the new moon period—to hunt prey with greater stealth. Given the absence of larger predators (specifically other sharks) in PKD Bay, our results suggest that juvenile sand tigers may travel to this area to feed and grow during the warm summer months.

As is often the case when conducting research on marine animals, additional data are required to confirm our hypotheses and to determine if similar activity patterns are evident in other juvenile sand tiger hangouts along the Massachusetts coast. Nonetheless, our work in PKD Bay has provided some great clues as to why these small sharks travel hundreds to thousands of miles to spend their summers off the Massachusetts coast.

Read more about this work in the Environmental Biology of Fishes.

Study participants: Dr. Jeff Kneebone (Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium), Megan Winton (University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, School for Marine Science and Technology), Dr. Andy Danylchuk (University of Massachusetts Amherst), John Chisholm and Dr. Greg Skomal (Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries).