Construction Update: As we enhance the look and feel of the Aquarium and make structural improvements to the penguin exhibit, some exhibits are temporarily closed, and the penguins are off exhibit until February 13. Learn more.

Tale of the Whiptail: Unlocking Mysteries of Common Thresher Shark Movements

Using pop-up satellite tags, researchers are filling in data gaps on thresher shark migration patterns in the North Atlantic.

A decade ago, if you asked even the most knowledgeable shark scientist to tell a tale of common thresher shark movements and migration in the North Atlantic, the story they penned would have been based more on speculation than fact. But now, after a decade–long research effort, the tale of common thresher shark—or whiptail as they are sometimes called by fishers in the Atlantic can be written with more facts than fiction.

Working on their own and in partnership with commercial and recreational fishers, a team of scientists from the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, NOAA Fisheries, and Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries deployed dozens of pop-up satellite archival (PSAT) tags on common threshers from North Carolina to the Canadian Grand Banks from 2016 to 2023. The team then partnered with scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to analyze the PSAT data and map the movements and migrations of the species in the North Atlantic Ocean.

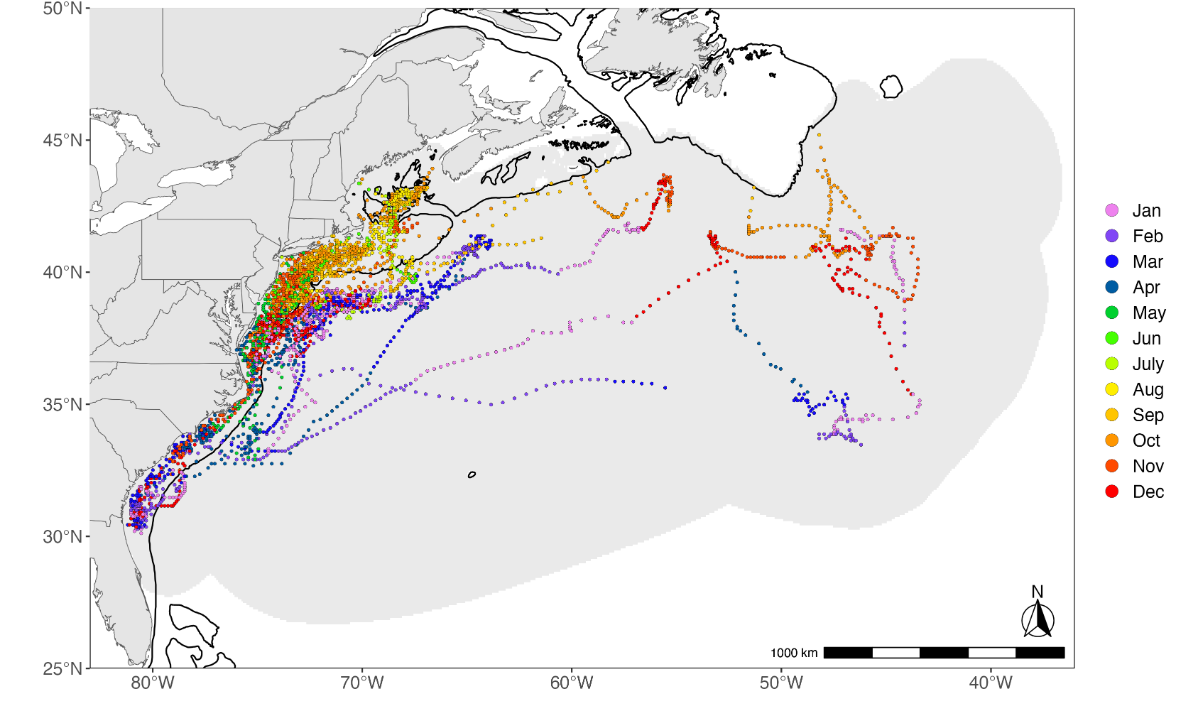

Corroborating what was discovered in a previous study that used fishery catch data to map common thresher shark distribution off North America, PSAT data revealed broad, seasonal migrations along the coast from Florida to the Canadian Grand Banks. In general, common thresher shark movements followed a typical “snowbird” pattern with movements toward more northerly latitudes occurring in the summer and then on to more southerly latitudes in the winter.

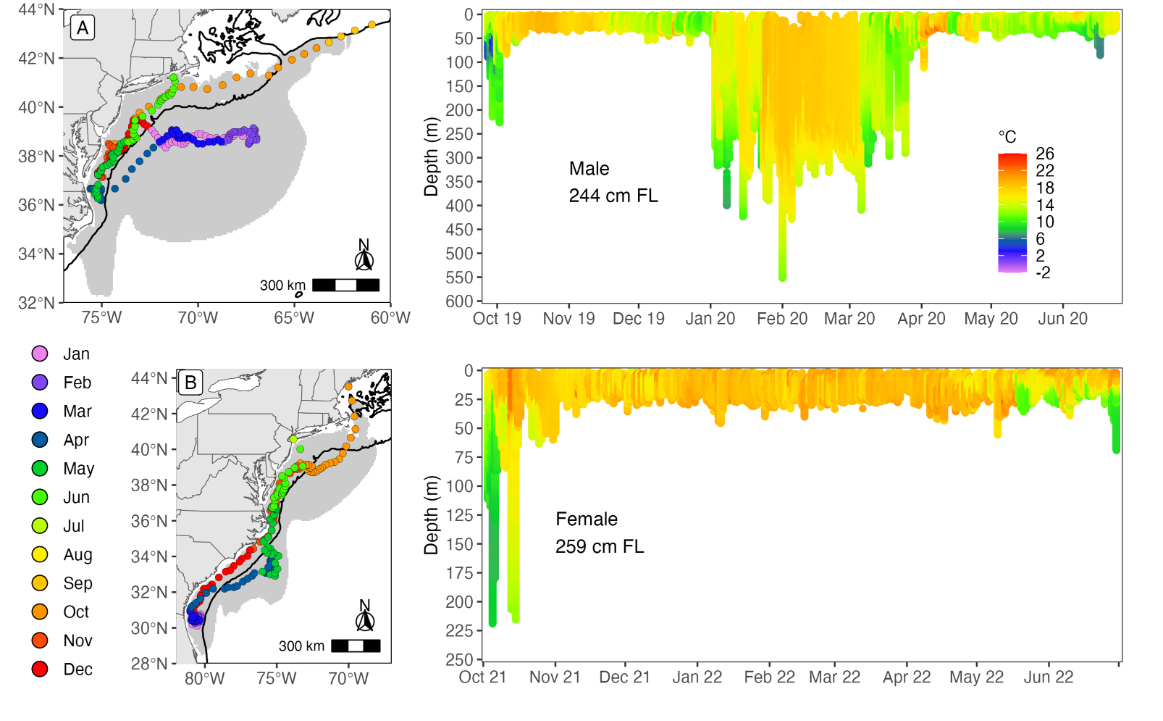

However, PSAT tracks also revealed extensive “inshore offshore” movements wherein some common thresher sharks moved from shallow, coastal waters to deep, offshore waters, particularly during the winter months. When they occur closer to the coast, common thresher sharks spend most of their time swimming at depths of less than 25 meters (around 80 feet). However, when they move offshore, farther away from the coast, they spend more than half their time swimming in depths from 100 to 600 meters (around 300 to 2,000 feet) and sometimes dive as deep as 1,800 meters, or almost 6,000 feet! Regardless of where they are in the ocean, common thresher sharks spend almost all their time in waters of 10 to 20ºC (around 50 to 70ºF), suggesting that this range is their physiological sweet spot.

Beyond providing novel information on common thresher shark ecology in the North Atlantic, the PSAT data will be useful for improving fishery management in the United States and Canada. In the absence of trans-Atlantic migrations—that is, movements across the North Atlantic to European waters—the tagging data suggest that common thresher sharks found off the east coast of North America may represent a distinct population that is separate from common thresher shark populations that occur off Europe. When combined with the finding that common thresher shark seasonal migration primarily occurs in US territorial waters, fishery regulators should consider managing the species akin to a coastal shark species that is mostly restricted to domestic waters rather than one that regularly traverses international boundaries.

You can read more about how PSAT tag data solved the mystery of common thresher shark movements in a paper published in the journal Marine Ecological Progress Series.

Research team:

- Jeff Kneebone (Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life)

- Diego Bernal (University of Massachusetts Dartmouth)

- Lisa Natanson (NOAA Fisheries, Apex Predators Program; retired)

- Greg Skomal (Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries)

- Martin Arostegui and Camrin Braun (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)