On Thursday, February 12, the Trust Family Foundation Shark and Ray Touch Tank will be closed until 10:30 a.m. for routine animal care

Construction Update: As we enhance the look and feel of the Aquarium and make structural improvements to the penguin exhibit, some exhibits are temporarily closed, and the penguins are off exhibit until February 13. Learn more.

Our History and What’s Ahead: Right Whale Research

40 Years (and Counting) of North Atlantic Right Whale Research

A history of protecting right whales

Since 1980, the New England Aquarium and our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life have led research efforts on the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale. Our work started over 40 years ago in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Since then, as right whales have shifted their summer habitat use to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, we’ve continued to have a research presence in the region, collaborating with other institutions to collect essential data on right whale health.

Our impact extends beyond the Northeast. In 1985, with the help of volunteer pilots, a team from the Aquarium discovered what is now known as the calving ground in the southeastern US and helped develop a monitoring strategy for new calves that is still in use today.

The Aquarium is also a founding member of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, which has served as a cornerstone for right whale research and conservation since 1986. The Consortium gathers yearly and publishes right whale population estimates, work that is made possible by the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog. Managed by our Anderson Cabot Center scientists, the Catalog contains more than two million photographs, creating an invaluable resource to track individual right whales throughout their lives.

Right Whale Drone Footage

Captured by Scientists from our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life

Innovating for the future

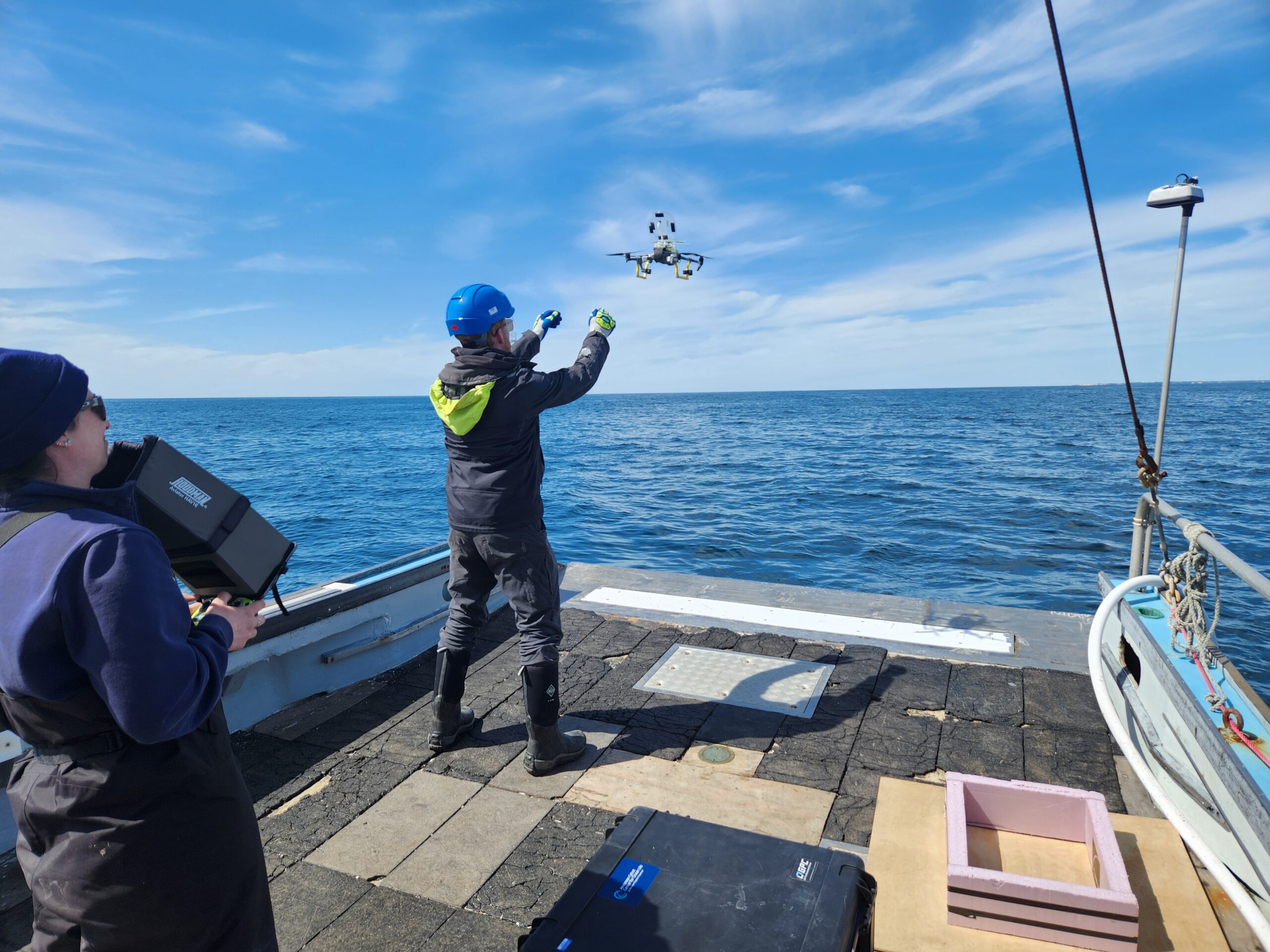

In Cape Cod Bay this past spring, Anderson Cabot Center researchers deployed the latest technology—drones, which the team uses to photograph and collect samples of blow.

Assistant Research Scientist Amy Warren and Associate Research Scientist Monica Zani are the team’s drone pilots, having received hours of training to conduct flights on a research vessel near these endangered animals. Research Scientist Hansen Johnson and Research Technician Kate McPherson also worked aboard the vessel, directing Warren and Zani toward whales as they piloted and catching the drone as it returned to the boat.

“The drone really revolutionizes the amount of information you can get non-invasively,” Johnson said. Work that usually requires research vessels to get close to the whales, which can be stressful for both humans and animals, can now be accomplished remotely. To collect blow samples, for example, pilots fly the drone above the whale as it exhales, and the sample is caught on a petri dish. This type of sampling isn’t just new to the team but new in the field—and the Aquarium is at the leading edge. Anderson Cabot Center scientists use these blow samples to assess individual right whales’ health, adding to our knowledge and guiding species conservation.

More possibilities are on the horizon, including drone-based photogrammetry (collection of length and girth measurements), suction-cup tagging, and thermal imagery. Video from drones can also help responders understand the configuration of a whale’s entanglement, increasing the chance of a successful disentanglement. Each technological advancement can make a meaningful difference for the species.

“We’re really at the beginning,” Johnson added. “Drones as a tool for marine science are here to stay, and their use is just in its infancy.”

Continuing our legacy

What will the next 40 years of right whale research bring? Each calf carries hope for the future of the species—and our scientists remain steadfast in their dedication to protecting right whales. With support and collaboration from other organizations, industry, government, and the public in efforts to eliminate human-caused threats to right whales, scientists believe the species can rebound.

As Hamilton told a crowd during the second annual Massachusetts Right Whale Day celebration at the Aquarium, “Each North Atlantic right whale holds a rich legacy, and it is our role to remember, acknowledge, respect, and protect these animals.”

This story originally appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of blue member magazine.