Get to Know Some of the Sharks We Study

By New England Aquarium on Friday, July 21, 2023

Shark research is an important part of the Aquarium’s marine science and conservation work. Here, get to know some of the sharks (and one type of skate!) we study and how we help inform protections of these ocean animals.

Nurse sharks

For over thirty years, Adjunct Scientist Wes Pratt has been studying nurse sharks on their breeding ground in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida. Senior Scientist Dr. Nick Whitney has been involved in the study for over 20 years, and the two work closely with Aquarium researchers and husbandry experts, including Associate Research Scientist Dr. Ryan Knotek, Senior Aquarist Lindsey Phenix, and Giant Ocean Tank Manager Mike O’Neill. This research is one of the longest ongoing studies of sharks in a single environment and has highlighted the importance of this marine habitat.

Nurse sharks are a benthic species, meaning they spend most of their time near the bottom of the water—but as part of this study, the team documented a nurse shark nicknamed “Starr” following dolphins as it hunted for food!

Sandbar sharks

Caroline Collatos, a PhD student and shark researcher with the Aquarium, has spent several summers tagging sandbar sharks off the coast of Nantucket. Her goal is to gather data about the sharks’ annual presence, habitat use, and migration patterns to better understand their behavior and population trends each year.

Sandbar sharks spend most of their time in coastal waters and are one of the largest species of coastal sharks!

Epaulette sharks

Aquarium visitors can see epaulette sharks up close in our Shark and Ray Touch Tank. They are one of the nine species of “walking sharks” and have evolved to use their strong pectoral fins to “walk” across the seafloor. In the wild, they live in Pacific coral reefs, including the Great Barrier Reef—a habitat that faces serious threats from climate change and rising ocean temperatures.

Dr. Carolyn Wheeler led the work as a PhD student at the Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life Animal Care, teaming up with Animal Care colleagues to better understand how these little sharks are affected by the changing climate. Animal Care staff at the Aquarium collected egg cases from the exhibit, transferring them to our Quincy facility, where the team maintained an epaulette shark breeding program.

There, the eggs were incubated in different temperature gradients. Results showed that warmer waters caused the baby sharks to be born smaller, exhausted, and undernourished, making it harder for the sharks to thrive. Their results underscored the importance of combating climate change to ensure the health of epaulette sharks and other marine species.

Sand tiger sharks

Sand tiger sharks range all along the US East Coast, from Maine to Florida, and can be found globally in waters from the Pacific and Indian oceans to the Mediterranean. They became a federally protected species in 1997 after experiencing a significant population decline in the US.

Over the past few years, Senior Scientist Dr. Jeff Kneebone and Dr. Knotek worked to tag sand tiger sharks in Quincy Bay, right in Boston Harbor. Their ongoing research has shown that these sharks may be using local waters as a nursery—and that their population appears to be rebounding. The movement data from the tags can help researchers better understand where the sharks travel and where additional protections for marine life might be needed.

Sand Tiger Shark Tagging and Monitoring

Scientists at the New England Aquarium's Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life work to tag and monitor sand tiger sharks in order to understand the importance of annually returning to a habitat during the sharks' long-distance migration.

Porbeagle sharks

Porbeagle sharks can be found in New England waters year-round and are relatives of the mako shark and white shark. On rare occasions, porbeagle sharks have washed up on local beaches—and that’s when Adjunct Scientist and shark expert John Chisholm answers the call. Collecting samples from necropsied sharks can help researchers learn more about these fish, including how they’re affected by ocean use and the effects of climate change.

Dr. Knotek also works to tag and track porbeagle sharks, evaluating the effects of accidental bycatch on the species and contributing data to help both commercial fisheries and local sharks thrive.

Thresher sharks

Thresher sharks get their name from their distinctive tail fin, which looks a bit like a scythe or thresher.

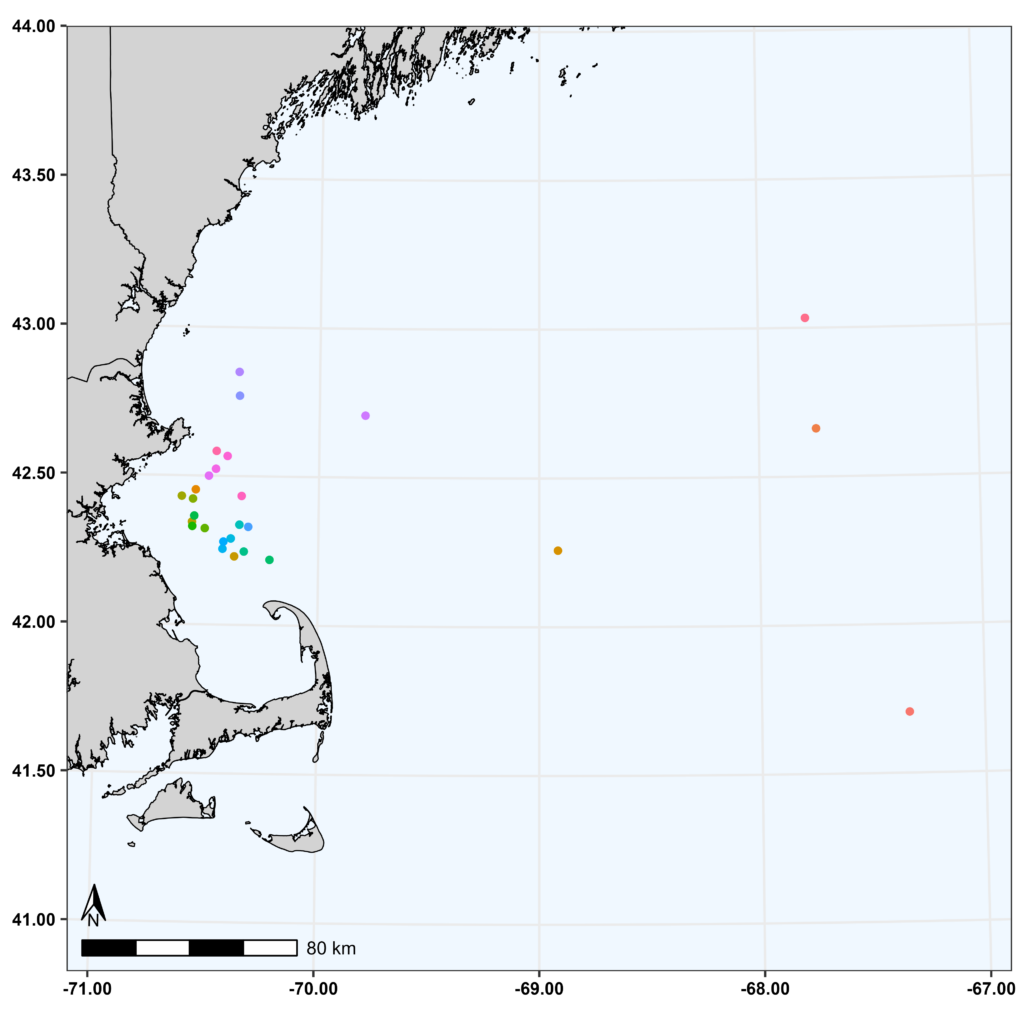

Here in New England, Dr. Kneebone has been part of a group of researchers working to understand thresher shark distribution in waters from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. These data are critically needed to inform fisheries management of this species along the US east coast.

Across the globe, Marine Conservation Action Fund fellow Rafid Shidqi leads the Thresher Shark Project Indonesia, an initiative to transition communities from traditional shark hunting to sustainable alternative livelihoods using research, stakeholder engagement, and education.

Spinner sharks

Spinner sharks are a highly migratory species found in coastal waters from the Gulf of Mexico to Southern New England. These sharks are targeted by recreational anglers as an exciting species to catch, often displaying high-flying acrobatics, leaping and spinning through the air.

But because spinner sharks are often caught and released, fisheries managers need to understand the impact fishing has on this species—a topic Dr. Knotek tackles in his research. He recently traveled to Georgia to tag spinner sharks, tracking and studying their movements to help determine their survival rates following catch-and-release in the recreational fishery.

Bull sharks

Bull sharks live in warm, shallow waters all over the world and can even survive in freshwater, sometimes traveling many miles up coastal rivers.

Dr. Knotek and Dr. Whitney are starting a project studying the post-release mortality and behavioral recovery of bull sharks in recreational fisheries in the Southeast. They plan to partner with local fishing charters in Florida to satellite tag the sharks, monitoring their movement. The survival information from this project can inform management regulations for bull sharks in the fishery and help identify best fishing practices to promoting the healthy release of these sharks.

Oceanic whitetip sharks

Once one of the most common shark species in the warmer waters of the open ocean, oceanic whitetip sharks are now one of the most overfished species in the world—only 2% of their global population remains. The international fin trade was largely responsible for the overfishing, but oceanic whitetip sharks have also, and continue to be, accidentally captured as bycatch in commercial fisheries.

In collaboration with the Oceanic Whitetip Consortium, Dr. Knotek, along with Dr. Kneebone and Chief Scientist Dr. John Mandelman, led a study to understand how fishing affects the health and survival of oceanic whitetip sharks when caught and released. Their work can help inform fisheries-specific strategies for mitigating mortality for this imperiled species.

Thorny skates

One of the most interesting sharks in New England Waters isn’t a shark at all, but a close shark relative—the thorny skate! Dr. Kneebone has been working to tag thorny skates in the Gulf of Maine in a cooperative effort with local fishers that has been going on for over twenty years. The research is helping to better understand the thorny skates’ movements and if they are traveling in Canadian waters where they are less protected.

Sharks, skates, and rays are closely related and make up a group called the elasmobranchs (E-las-mo-branks).

White sharks

White sharks capture a lot of attention during the summer, especially along the coast of Cape Cod, where their numbers have rebounded over the years. The Aquarium partners with the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy to help process white shark sightings for their Sharktivity app. John Chisholm partners with the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy to verify white shark sightings reported by the public and collects key information before sightings are published in the app.